AI Literacy or AI Literacies?

Exploring the plural, context-dependent, and socially-negotiated nature of new literacies

Exploring the plural, context-dependent, and socially-negotiated nature of new literacies

Over the past couple of months, we’ve been working on an ‘AI Literacy’ project with the Responsible Innovation Centre for Public Media Futures (RIC), hosted by the BBC. We’ve already published:

- What does AI Literacy look like for young people aged 14–19?

- What makes for a good AI Literacy framework?

- Core Values for AI Literacy

In this post, we want to explore the tension we’ve felt between referring to ‘AI Literacy’ in the singular, versus referring to a plurality of ‘AI Literacies’. Ultimately, although our original brief used the singular form (as do many of our peers) we have decided to take the latter, plural, approach — for reasons we will explain below.

One very practical reason to emphasise ‘AI Literacies’ is that it is difficult to talk about ‘delivering’ a literacy. “Literacy” always begs the question of context: What does literacy mean to this particular person in this particular setting at this particular moment? What it means to be ‘AI literate’ is going to look very different to someone working in a corporate office job, compared to a teenager using AI for a creative project. Additionally, there are multiple literate behaviours when we think about AI — for example, understanding the socio-economic reality of the AI landscape versus knowing how to prompt an LLM to get the kind of information or answer you are looking for.

AI Literacies are therefore both plural and context-specific. They are also socially-negotiated. Literate behaviours depend on the community with which an individual is interacting. This becomes evident through a few examples.

If you are a parent of teenagers, you will have experienced a time when they respond in a way which makes sense to them and their friends, but not to you. You are likely to have to ask them what they mean or use a resource like the Urban Dictionary. Other behaviours such as using a particular emoji might be hilarious for reasons you cannot quite comprehend.

These “rhetorics of communication” are an important part of literacy practices, especially in the digital realm. They constitute ways of interacting with other people within a techno-social system which itself privileges and foregrounds certain kinds of behaviours, while either explicitly or implicitly discouraging others. For example, contemporary chat apps allow you to see not only that a message has been delivered, but whether it has been read. The act of not reading a particular message may be seen in multiple lights: Is the person ignoring me? Are they mad at me? Are they offline in the forest?

Any time we are communicating in ways which are mediated by technologies, part of literate behaviour involves understanding the “affordances” that the technology provides as well as understanding how that technology might be shaping our behaviour.

If you were, for example, quickly texting your teenager while at work, you might send your text and then open a workplace chat window which looks and feels very much like the social one which you have just been using. However, because the context is different — as well as perhaps both the demographic makeup and number of people in the chat — you act differently. =Your literate behaviours are thus socially-negotiated, meaning that you vary your behaviour in different situations.

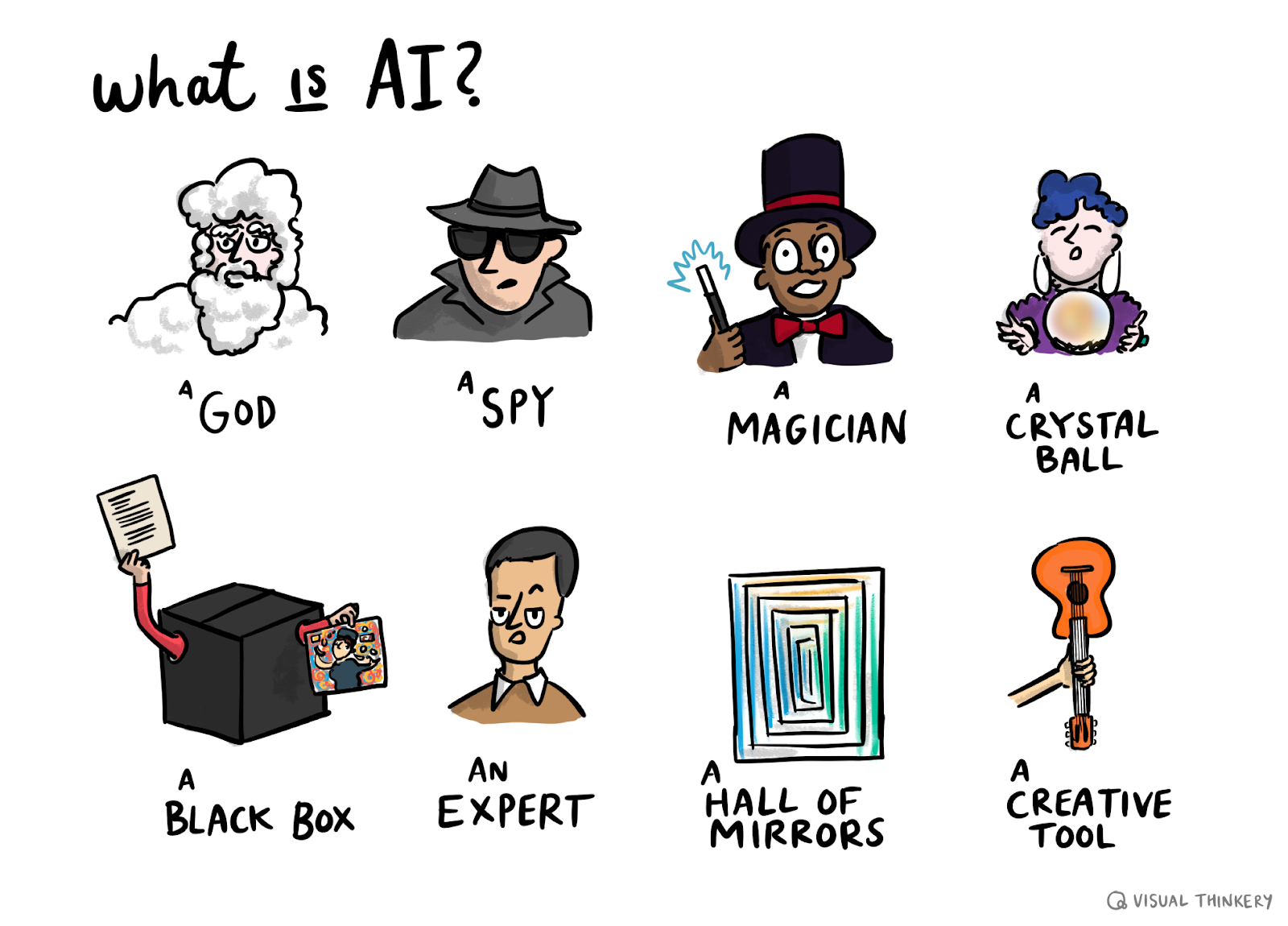

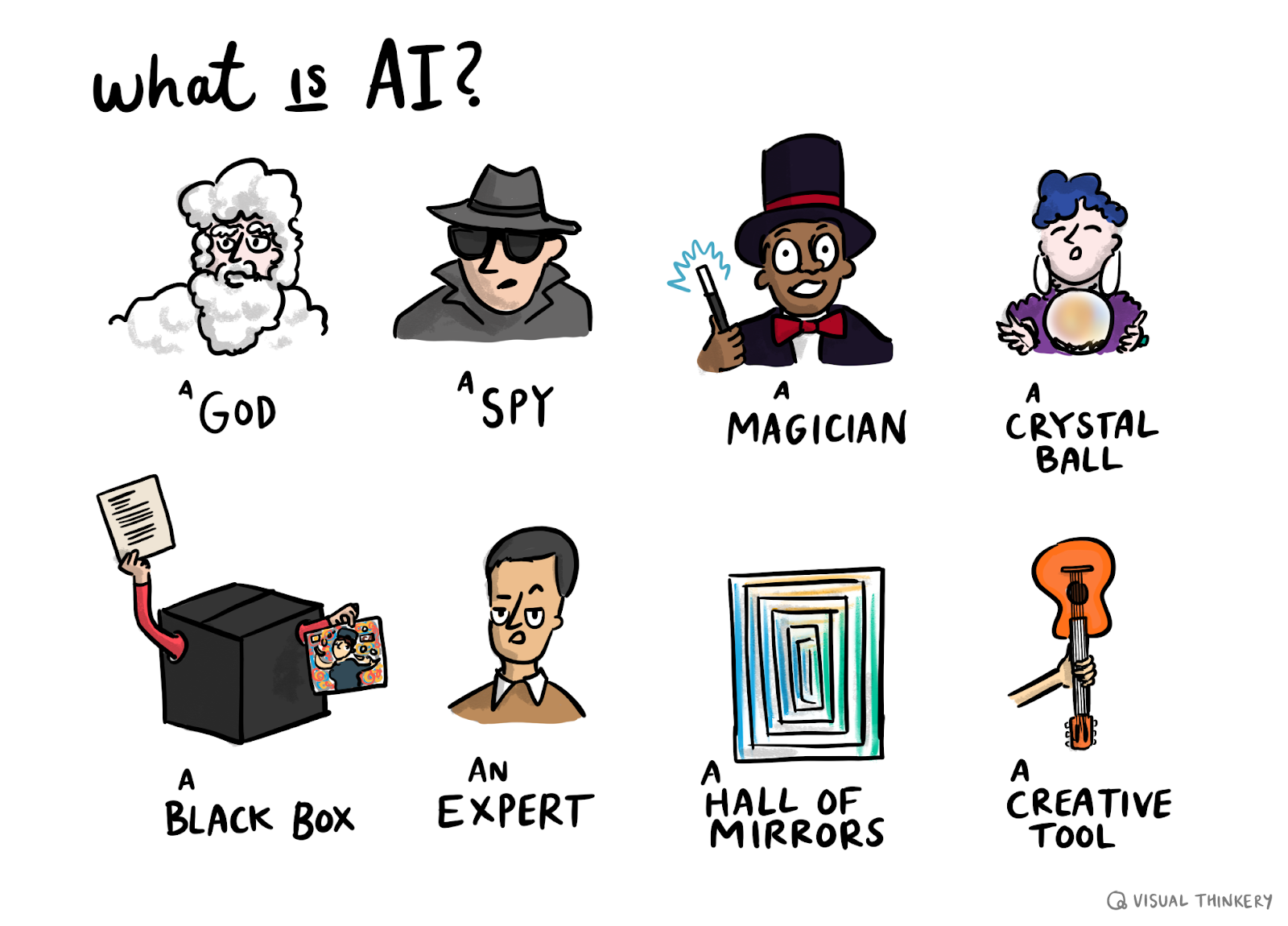

As we start to understand AI Literacies, we need to think about the most common way in which people experience generative AI — by prompting a Large Language Model (LLM) through a chat window. The chat window is a familiar technology, but the fact that there isn’t a human on the other side of it is not. Part of AI Literacies therefore involves exhibiting and modifying our behaviours based on our knowledge and experience of factors that surround this particular chat window.

With personal or workplace chats, what is outside of the frame informs literate behaviours inside the frame. Similarly, when we are interacting with AI, the more we know about what is outside the frame, the more we can develop appropriate literate behaviours inside the frame. Again, these literate behaviours are plural: will others be able to tell that you are using the outputs of an LLM? (will they mind?) They are based on context: should you trust the company behind the technology you are using? And they are socially-negotiated: are there environmental concerns of which you should be aware?

Angela Gunder’s Dimensions of AI Literacies provides a helpful way to think about these issues. Building on my work on the Essential Elements of Digital Literacies, Gunder’s framework sets out a series of overlapping dimensions that shape how people interact with AI. This approach supports the idea that AI Literacies are not a fixed set of skills, but a collection of practices negotiated within communities and shaped by context.

AI Literacies, like Critical Media Literacies, Digital Literacies, Information Literacies, Data Literacies, and a whole host of “new” literacies, should be considered to be fundamentally plural. What counts as “literate behaviours” are socially-negotiated based on context. Words and phrases, however, are important to describe what we mean. And that is why we will be referring to AI Literacies in the project we’re doing with the RIC for the BBC.

Coming soon

We are working on a public version of our landscape setting and framework for AI Literacies. We’ll be sharing that soon. In the meantime, follow our contributions to this space through https://ailiteracy.fyi/ and get in touch if you have projects and programmes that can benefit from our experience and expertise in education and technology.

Discussion