This is the first post in a series exploring the fundamentals of Systems Thinking. This is an approach that helps us make sense of complex situations by considering the whole system rather than just its individual parts.

Why is Systems Thinking important? Whether you’re navigating challenges in your professional life or making decisions in your personal life, Systems Thinking offers a series of powerful lenses through which to view the interconnectedness of various elements. By understanding how different parts of a system influence one another, you can identify more effective solutions, anticipate unintended consequences, and make better-informed decisions. This holistic approach is particularly valuable in today’s complex world, where problems are rarely isolated and simple fixes can often lead to new issues!

This series is made up of:

- Part 1: Three Key Principles (this post)

- Part 2: Understanding Feedback Loops

- Part 3: Identifying Leverage Points

In this first post, we’ll explore three key principles that are foundational to a Systems Thinking approach: Drawing a Boundary, Multiple Perspectives, and Holistic Thinking. These principles provide the groundwork for seeing beyond surface-level problems and understanding the deeper, often hidden, relationships and patterns within any system. By applying these principles, you can begin to approach challenges with a mindset that seeks to comprehend the whole rather than merely addressing symptoms, leading to more sustainable and impactful solutions.

1. Drawing a boundary

“The only problems that have simple solutions are simple problems. Complex problems have complex solutions.” — Russell Ackoff

In Systems Thinking, one of the first steps is to draw a boundary around the system you’re examining. This boundary defines what is included within the system and what is considered external. It’s crucial because the way you set this boundary determines the scope of your analysis and influences the insights you gain.

A boundary can be drawn in various ways. It might cut cross-functionally across an organisation, considering multiple departments and their interactions. Alternatively, it could include several organisations, looking at an entire ecosystem rather than a single entity. These choices lead to different conclusions and strategies. Boundaries help manage complexity by allowing you to concentrate on specific parts of the system without getting overwhelmed by the whole.

For example, when we started working with the Digital Credentials Consortium (DCC) based at MIT, we had to make a decision about where to draw the boundary. We could have drawn it very narrowly to focus just on the DCC team, which would have focused mainly on operational issues and decision-making. Our brief, however, was to help with a communications strategy, which meant drawing a wider one. This included organisations who were aware of the DCC, but not directly involved with them.

Draw a boundary too wide, and it becomes difficult to identify ways to create meaningful change. For example, if we included all of Higher Education, it would have become an impossible project to manage. In the end, we identified key stakeholder groups (e.g. registrars) and included them within the boundary. That meant purposely excluding other stakeholders (e.g. vendors) so that we could work on communications that would resonate and create change.

2. Multiple perspectives

“We live in a world of problems, not puzzles. Problems are tangled with uncertainty, ambiguity, and value conflicts.” — Geoffrey Vickers

Every system is viewed differently depending on the perspective of the observer. Recognising and incorporating multiple perspectives is a cornerstone of Systems Thinking. Each stakeholder sees the system from their own unique angle, and by considering these diverse viewpoints, we can uncover hidden dynamics and potential conflicts.

For instance, with the DCC project, we needed to gain the perspectives of different members of the team, the Leadership Council, and key stakeholder groups. Each had different opinions and concerns, which helped us create an effective and holistic communications plan, balancing the needs of all stakeholders and provide a way forward.

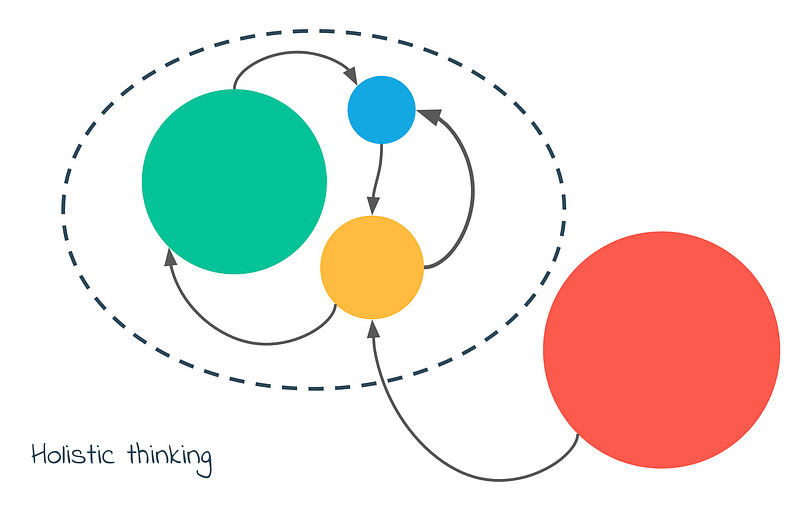

3. Holistic thinking

“Insight, I believe, refers to the process by which a shift in perspective reveals a coherent pattern that had previously been obscured from view.” — Mary Catherine Bateson

Holistic thinking involves seeing the system as a whole rather than just focusing on individual parts. It contrasts with reductionist approaches, which break down a system into its components. While reductionism can be useful, it often misses the interactions and relationships that make the system function.

In the DCC communications strategy project, it was important not to take a reductionist approach focused on individual aspects, but rather think more holistically. We needed a way that considered how these elements interact. For example, by creating a cadence for communications which re-uses content from one platform, and which helps scaffold stakeholder understanding. By considering the Verifiable Credentials ecosystem as an interconnected whole, we were able to think about how a communications strategy could encourage adoption, without burning out DCC staff.

Conclusion

In this post, we’ve explored the three foundational pillars of Systems Thinking: Drawing a Boundary, Multiple Perspectives, and Holistic Thinking. These principles offer a powerful framework for tackling complex problems, allowing you to see the bigger picture, understand diverse viewpoints, and recognise the intricate connections that drive systems. By applying these concepts, you can develop more effective strategies, avoid unintended consequences, and create sustainable solutions.

At We Are Open Co-op, we specialise in helping organisations integrate these Systems Thinking principles into their everyday practices. Whether you’re navigating organisational change, developing strategies, or addressing societal challenges, our approach can help you uncover deeper insights and achieve lasting impact.

If you’re interested in how Systems Thinking can transform your organisation, we’d love to collaborate with you. Stay tuned for the next post in this series, where we’ll delve into practical applications of these principles, providing you with tools and examples to put Systems Thinking into action.

References

- Ackoff, R.L. (1974). Redesigning the Future: A Systems Approach to Societal Problems. New York: Wiley.

- Bateson, M.C. (1994). Peripheral Visions: Learning Along the Way. New York: HarperCollins.

- Beer, S. (1972). Brain of the Firm. New York: Herder and Herder.

- Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), pp. 127–138.

- Vickers, G. (1965). The Art of Judgement: A Study of Policy Making. London: Chapman & Hall.

Discussion