WAO is currently working with the Responsible Innovation Centre for Public Media Futures (RIC), which is hosted by the BBC. The project, which you can read about in our kick-off post, is focused on research and analysis to help the BBC create policies and content to help improve the AI Literacy skills of young people aged 14–19.

We’re now at the stage where we’ve reviewed academic articles and resources, scrutinised frameworks, and reviewed input from over 40 experts in the field. They are thanked in the acknowledgements section at the end of this post.

One of the things that has come up time and again is the need for an ethical basis for this kind of work. As a result, in this post we want to share the core values that inform the development of our (upcoming) gap analysis, framework, and recommendations.

Public Service Media Values

Public Service Media (PSM) organisations such as the BBC have a mission to “inform, educate, and entertain” the public. The Public Media Alliance lists seven PSM values underpinning organisations’ work as being:

- Accountability: to the public who fund it and hold power to account

- Accessibility: to the breadth of a national population across multiple platforms

- Impartiality: in news and quality journalist and content that informs, educates, and entertains

- Independence: both in terms of ownership and editorial values

- Pluralism: PSM should exist as part of a diverse media landscape

- Reliability: especially during crises and emergencies and tackling disinformation

- Universalism: in their availability and representation of diversity

These values are helpful to frame core values for the development of AI Literacy in young people aged 14–19.

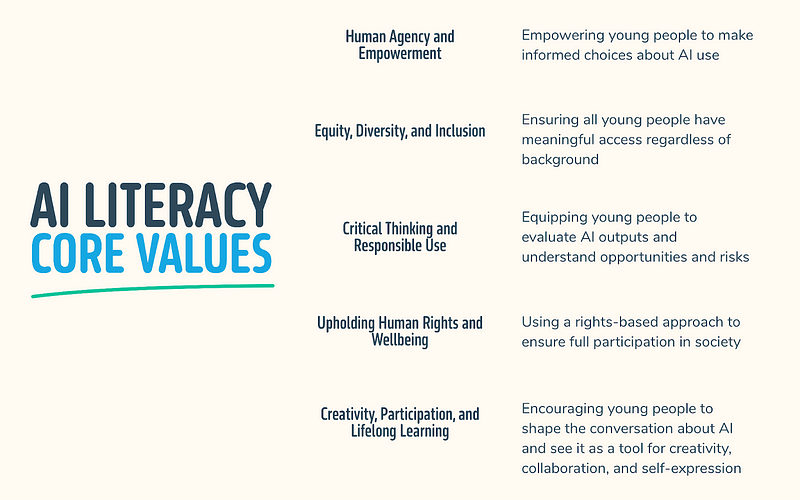

AI Literacy Core Values

Using the PSM values as a starting point, along with our input from experts and our desk research, we have identified the following core values. These are also summarised in the graphic at the top of this post.

1. Human Agency and Empowerment

AI Literacy should empower young people to make informed, independent choices about how, when, and whether to use AI. This means helping develop not just technical ability, but also confidence, curiosity, and a sense of agency in shaping technology, rather than being shaped by it (UNESCO, 2024a; Opened Culture, n.d.). Learners should be encouraged to question, critique, adapt, and even resist AI systems, supporting both individual and collective agency.

2. Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

All young people, regardless of background, ability, or circumstance should have meaningful access to AI Literacy education (Digital Promise, 2024; Good Things Foundation, 2024). Ensuring this in practice means addressing the digital divide, designing for accessibility, and valuing diverse perspectives and experiences. Resources and opportunities must be distributed fairly, with particular attention to those who are digitally disadvantaged or underrepresented.

3. Critical Thinking and Responsible Use

Young people should be equipped to think critically about AI, which means evaluating outputs, questioning claims, and understanding both the opportunities and risks presented by AI systems. In addition, young people should be encouraged to understand the importance of responsible use, including understanding bias, misinformation, and the ethical implications of AI in society (European Commission, 2022; Ng et al., 2021).

4. Upholding Human Rights and Wellbeing

Using a rights-based approach — including privacy, freedom of expression, and the right to participate fully in society — helps young people understand their rights, navigate issues of consent and data privacy, and recognise the broader impacts of AI on wellbeing, safety, and social justice (OECD, 2022; UNESCO, 2024a).

5. Creativity, Participation, and Lifelong Learning

AI should be presented as a tool for creativity, collaboration, and self-expression, not just as a subject to be learned for its own sake. PSM organisations should value and promote participatory approaches, encouraging young people to contribute to and shape the conversation about AI. This core value also recognises that AI Literacy is a lifelong process, requiring adaptability and a willingness to keep learning as technology evolves (UNESCO, 2024b).

Next Steps

We will be running a roundtable for invited experts and representatives of the BBC in early June to give feedback on the gap analysis and emerging framework. We will share a version of this after acting on their feedback.

If you are working in the area of AI Literacy and have comments on these values, please add them to this post, or get in touch: hello@weareopen.coop

Acknowledgements

The following people have willingly given up their time to provide invaluable input to this project:

Jonathan Baggaley, Prof Maha Bali, Dr Helen Beetham, Dr Miles Berry, Prof. Oli Buckley, Prof. Geoff Cox, Dr Rob Farrow, Natalie Foos, Leon Furze, Ben Garside, Dr Daniel Gooch, Dr Brenna Clarke Gray, Dr Angela Gunder, Katie Heard, Prof. Wayne Holmes, Sarah Horrocks, Barry Joseph, Al Kingsley MBE, Dr Joe Lindley, Prof. Sonia Livingstone, Chris Loveday, Prof. Ewa Luger, Cliff Manning, Dr Konstantina Martzoukou, Prof. Julian McDougall, Prof. Gina Neff, Dr Nicola Pallitt, Rik Panganiban, Dr Gianfranco Polizzi, Dr Francine Ryan, Renate Samson, Anne-Marie Scott, Dr Cat Scutt MBE, Dr Sue Sentance, Vicki Shotbolt, Bill Thompson, Christian Turton, Dr Marc Watkins, Audrey Watters, Prof. Simeon Yates, Rebecca Yeager

References

- Digital Promise (2024). AI Literacy: A Framework to Understand, Evaluate, and Use Emerging Technology. https://doi.org/10.51388/20.500.12265/218

- European Commission (2022) DigComp 2.2, The Digital Competence framework for citizens. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2760/115376.

- Good Things Foundation (2024) Developing AI Literacy With People Who Have Low Or No Digital Skills. Available at: https://www.goodthingsfoundation.org/policy-and-research/research-and-evidence/research-2024/ai-literacy

- Jia, X., Wang, Y., Lin, L., & Yang, X. (2025). Developing a Holistic AI Literacy Framework for Children. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–16). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3727986

- Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Chu, S. K. W., & Qiao, M. S. (2021). Conceptualizing AI literacy: An exploratory review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 2(100041), 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2021.100041

- OECD (2022) OECD Framework for Classifying AI Systems. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-framework-for-the-classification-of-ai-systems_cb6d9eca-en.html

- Opened Culture (n.d.) Dimensions of AI Literacies. Available at: https://openedculture.org/projects/dimensions-of-ai-literacies

- Open University (2025) A framework for the Learning and Teaching of Critical AI Literacy skills. Available at: https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/learning-design/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/OU-Critical-AI-Literacy-framework-2025-external-sharing.pdf

- UNESCO (2024a) UNESCO AI competency framework for students. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391105

- UNESCO (2024b) UNESCO AI Competency Framework for Teachers. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391104

Discussion