We’re publishing this in the wake of mass layoffs in the tech industry, with some people finding out in particularly cruel ways that their employment has been terminated.

With that as a touchpoint, in this post we want to dig into what Open Workplace Recognition actually looks like in practice. We’ll have a look at what motivates us in the workplace and what Open Workplace Recognition could look like in different types of organisations.

Recognition as a driver

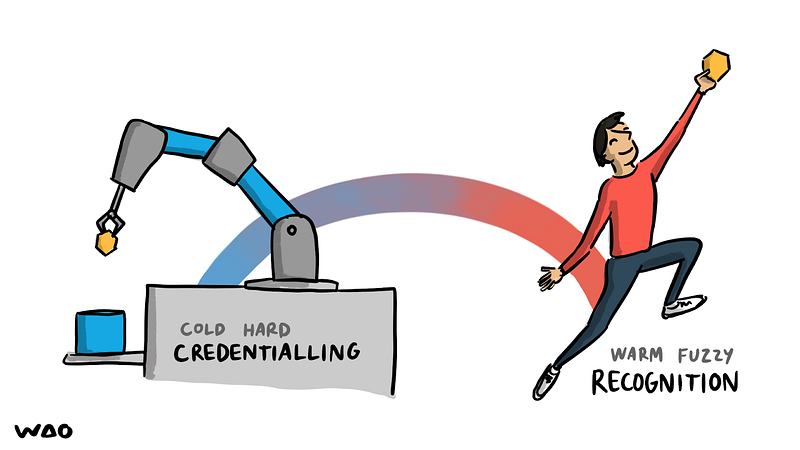

Let’s just quickly remind ourselves what we mean by Open Recognition:

“Open Recognition is the awareness and appreciation of talents, skills and aspirations in ways that go beyond credentialing. This includes recognising the rights of individuals, communities, and territories to apply their own labels and definitions. Their frameworks may be emergent and/or implicit.”

Credentials are usually things that you acquire to be able to unlock an opportunity or increase in status. So degree certificates, drivers licences, and even tickets for a concert can be thought of as ‘credentials’. These abound in the workplace: some group of people (usually ‘higher-ups’), decide what is important and create credentials in line with that strategy.

This post is not an argument that credentials should not exist. As we have argued elsewhere, the important thing to note is the role of recognition in the act of credentialing. Going further, we also encourage workplaces to think of non-credential forms of recognition.

Daniel Pink’s seminal work Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us explains that we have three basic needs at work:

- Autonomy — the desire to be self-directed and feel like we’re making meaningful choices.

- Mastery — the urge to continually improve our knowledge and skills.

- Purpose — the impulse to do something that is meaningful and important.

This is not how people tend to be “recognised” at work. ‘Recognition’ is often conflated with ‘reward’ and so we look to award ceremonies, promotions, and company-wide messages from managers for validation. Research shows, however, that these extrinsic rewards can actually replace people’s intrinsic motivation. So what are we to do?

There is a better way. It’s one that chimes more with the autonomy, mastery, and purpose mentioned above. It’s one that’s more peer-to-peer. And it’s one that can lead to portable, granular, and evidenced-based forms of recognition that employees can carry with them to their next job — whether or not that’s in the same organisation.

Recognition in practice

As we’ve said before, Open Recognition is for every type of learning and it’s for every type of workplace. So what does this mean in practice?

If we consider three types of workplace and reference different types of learning scenarios, we can begin to see the types of recognition that are required in each situation. Let’s dig in to find the similarities and differences between Open Workplace Recognition for employees, freelancers, and small business owners.

💼 Employees

Employees work for organisations that usually set policies without their input. These could be anything from job requirements and prerequisite skills through to salaries and vacation policies. Depending on the core business of the organisation and progression pathways, this could mean that it doesn’t take long for employees to lack not only autonomy, but mastery and purpose.

Sometimes, workplaces attempt to remedy this through spurious systems based on ‘points’ to reward colleagues. Our experience suggests this rapidly devolves into either a popularity contest or an empty exercise where colleagues give away all of their points to a peer as it’s the end of the month. Not only are these types of attempts at recognition wide of the mark, they’re actively demotivating.

Furthermore, employees cannot take any of this with them when you inevitably move on to a new organisation. (LinkedIn recommendations don’t quite cut it.) That’s why Open Workplace Recognition uses a nuanced approach based on Open Badges to recognise pro-social behaviours as well as knowledge and skills. For example:

- Sally has a line manager who notices that she showed up to every company event over the last year. Recognising her dedication her line manager issues Sally an ‘Above and Beyond’ badge.

- Akaash has learned a lot from his mentor Priya over the last couple of years, and so issues her a ‘Marvellous Mentor’ badge. She reciprocates by issuing him a badge which includes the LinkedIn recommendation she has already written for him.

- Junior is committed to professional development but his company’s policy comes with ‘strings attached’ meaning that paying for courses related to anything outside of his immediate job role cannot be sanctioned. One of his colleagues, Blessing, issues him an ‘Onwards and Upwards’ badge to recognise his dedication.

If the workplace functions more as a community of practice, then social learning is visible and recognised. It means that employees would feel more autonomy and mastery, and therefore consider their work to have more purpose.

👩💻 Freelancers

Freelancers deal with different kinds of recognition problems. They have to have business management and client acquisition skills in addition to whatever product or service they might be offering. These skills are often not recognised at all, with potential clients focusing only on the freelancer’s portfolio, including who they have worked with before. A freelancer’s ability to promote themselves and their work is also explicitly tied to social and cultural factors that they may be unable to control.

Freelancers may have formal learning credentials and might be able to point to some forms of recognition they have collected over the course of their career. However, if recognition is not a transferable feature of networking events, pro-bono work or career-related participation in a community, freelancers have to find their own ways of showcasing their engagement, talent and skill.

- Jayden funds himself to go to one networking event per month. He issues himself an attendance badge and asks the event organisers to ‘endorse’ it to add value.

- Valentina agrees to do some work for free to build her brand, but insists on a badge from the company proving her involvement in the project.

- Koko organises an online community for freelancers in her industry. She is issued a badge by an industry veteran who is thankful for her voluntary work.

Freelancers could benefit from Open Workplace Recognition between workplaces, and also by conceptualising their own work as happening within a ‘third place’ workplace. As a result, freelancers can be recognised not only by their clients but also by other freelancers, leading to increased autonomy (choosing when and how to work), mastery (being recognised for knowledge and skills development), and purpose (continuing to do what they love).

✊ Small businesses

A small agency, business or cooperative often offers more control for the people who work within it. Depending on the organisation and management of an agency, workers may have ways of recognising another that are built into the culture of the workplace.

Like employees and freelancers, workers in an agency are often initially recognised for their formal learning certification and career history. Just as with larger employers, an agency may use these certifications as a filtering function. And, like freelancers, non-transferrable recognition is often invisible to others within the different workplaces.

In an agency, a worker is required to advocate for themselves like a freelancer, while beholden to agency-wide decisions and policies like a more traditional employer.

- Shiro recognises that a new skillset is required for a new project coming into the agency, and so asks the agency for time to upskill. They are issued a series of badges recognising their increased levels of knowledge and skills.

- Mike attends dinners and events on behalf of his small business which often much later turn into business leads/opportunities. His colleagues recognise his networking skills by issuing badges.

- Lucas, Amahle, and Diego participate in communities related to growing the co-op movement. Their co-op not only pays them an internal rate for this time, but issues badges under Principle 6 (“cooperation among cooperatives”) of the ICA principles.

By thinking about small businesses and networks of small businesses such as agencies and co-ops as communities of practice, we can think of all of the ways that recognition may occur. There are many ways in which autonomy, mastery, and purpose can develop, especially in worker-owned businesses. However, recognition which is portable, granular, and evidence-based does not happen by accident.

Next steps

Are you interested in Open Workplace Recognition and what it could mean for organisations like your own? Do you have questions about how to get started with Open Badges that recognise pro-social behaviours? What kind of things do colleagues in your organisation really value?

We’re happy to answer any questions you may have in the comments section. But also, start asking your colleagues, experiment with badges, and join the KBW community!

Discussion