This is the third in a series of posts about Systems Thinking, an approach that helps us make sense of complex situations by considering the whole system rather than just the individual pieces from which it is constituted.

This series is made up of:

- Part 1: Three Key Principles

- Part 2: Understanding Feedback Loops

- Part 3: Identifying Leverage Points (this post)

In the first post, we laid the groundwork by exploring the foundational principles of Systems Thinking. We then explored feedback loops in the second post, examining how they drive system behaviour and contribute to stability or change.

In this concluding post, we turn our attention to Leverage Points — those critical areas within a system where a small shift can lead to profound changes. By understanding and identifying these points, you can uncover powerful opportunities for intervention, allowing you to drive meaningful and lasting change within complex systems.

1. What are leverage points?

“When we must deal with problems, we instinctively refuse to try the way that leads through darkness and obscurity. We wish to hear only of unequivocal results, and completely forget that these results can only be brought about when we have ventured into and emerged again from the darkness.” — Carl Jung

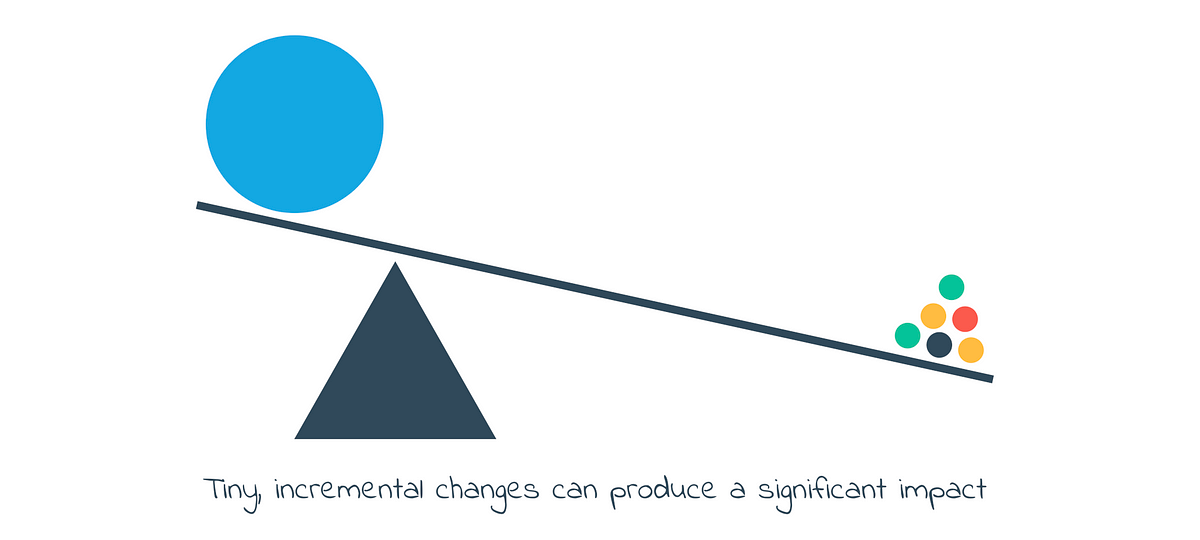

Leverage points are specific areas within a system where a small change can produce a significant impact on the entire system. These points often require careful analysis and a deep understanding of the system’s structure and behaviour, as they are not always immediately obvious. Identifying leverage points can be challenging because they are often hidden beneath the surface of the system’s visible components.

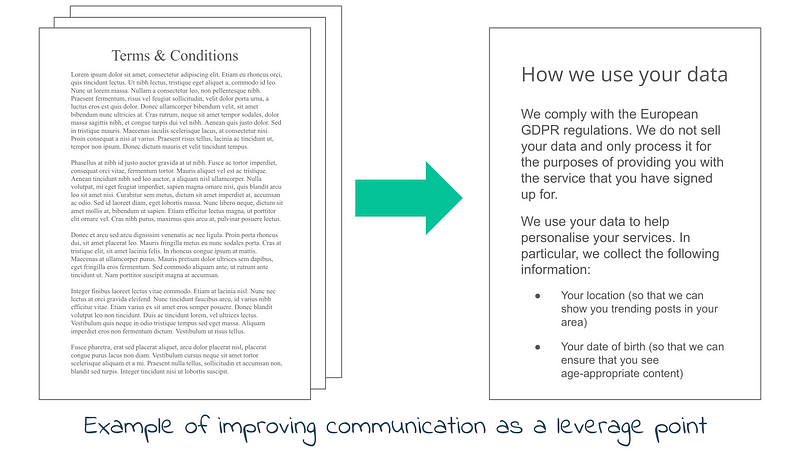

For example, in the world of technology, offering short, simple, clear (e.g. no legalese) ‘Terms and Conditions’ might be a leverage point. By helping users understand exactly how your organisation uses their data, you might improve customer satisfaction, increase trust, and reduce misunderstandings — all by making it easy for people to understand your company’s policy on privacy.

Leverage points, therefore, offer a way to create meaningful change by focusing on areas where even minimal effort can lead to substantial results. Recognising these points requires stepping back and viewing the system holistically, understanding not just the individual parts but how they interact and influence each other.

2. The role of paradigms in leverage points

“Inquiry is the controlled or directed transformation of an indeterminate situation into one that is so determinate in its constituent distinctions and relations as to convert the elements of the original situation into a unified whole.” — John Dewey

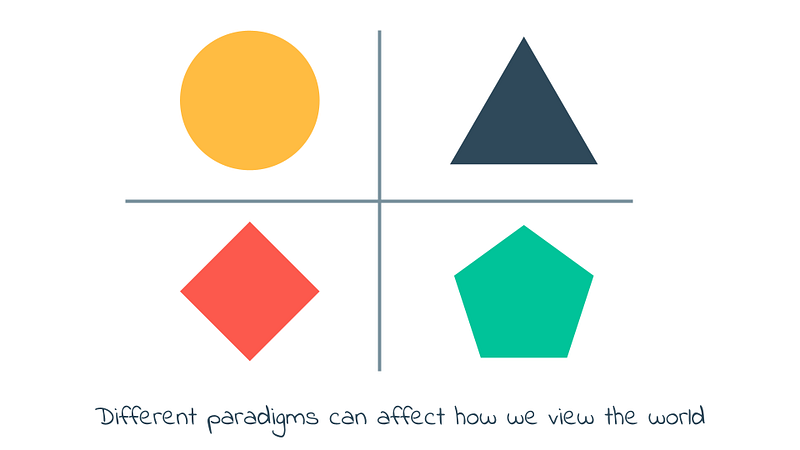

Paradigms are the underlying beliefs and assumptions that shape how we understand and interact with a system. These paradigms represent some of the most powerful leverage points, as changing a paradigm can fundamentally alter the way a system operates. Shifting these beliefs requires questioning what is often taken for granted and being open to new perspectives.

To go back to our Terms and Conditions example, a paradigm shift from prioritising user convenience to emphasising data privacy can serve as a transformative leverage point. Traditionally, many tech companies have focused on creating products that are easy to use, often at the expense of data privacy. However, as the paradigm shifts towards valuing privacy, we see significant changes in how technologies are designed and deployed.

This shift has been significantly driven by policy changes, such as the implementation of the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GDPR has forced companies to rethink how they collect, store, and manage user data, prioritising privacy by design. As a result, this new perspective has encouraged the development of more secure products, the adoption of stricter data management practices, and an overall increase in consumer trust. The influence of GDPR illustrates how policy can drive paradigm shifts, leading to widespread changes not just in product development but also in corporate strategies, legal frameworks, and consumer expectations. This example demonstrates the profound impact that changing a paradigm, supported by regulatory measures, can have on an entire system.

By addressing paradigms, especially through supportive policies, you are working at the root of the system’s behaviour. Changing the underlying beliefs that drive a system can lead to widespread and lasting change, making paradigm shifts one of the most effective leverage points in Systems Thinking.

3. Small, incremental changes as leverage points

“Of any stopping place in life, it is good to ask whether it will be a good place from which to go on as well as a good place to remain.” — Mary Catherine Bateson

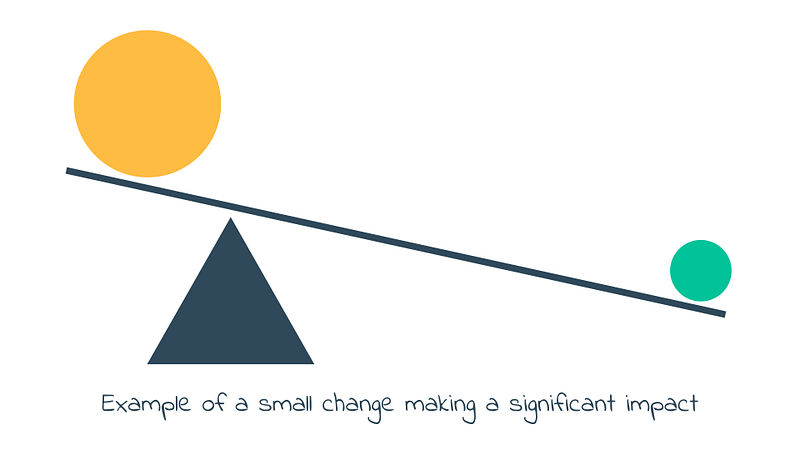

Small, well-placed actions can serve as powerful leverage points within a system. These might involve slight adjustments in policy, processes, or resource allocation. The key is to identify where these small changes can have a disproportionately large impact, leading to significant shifts in the system without the need for extensive interventions.

For example, in the context of data privacy, implementing a small but strategic change, such as requiring explicit user consent for data sharing, can have a profound impact. A great example of this is the introduction of GDPR-compliant consent forms across digital platforms in the EU. This seemingly minor policy change has led to a significant increase in user awareness and control over their personal data, contributing to greater trust in online services. The increased transparency and control have demonstrated how a small, well-placed policy change can lead to substantial benefits for both users and organisations, highlighting the power of incremental changes at the right leverage points.

The success of such small interventions lies in their ability to trigger widespread behavioural changes without the need for drastic overhauls. By carefully identifying and implementing these changes, we can achieve meaningful and lasting impacts across various systems.

4. Communication as a leverage point

“We are changed not only by being talked to but also by hearing ourselves talk to others, which is one way of talking to ourselves. More exactly, we are changed by making explicit what we suppose to have been awaiting expression a moment before.” — Geoffrey Vickers

Communication within a system can serve as a crucial leverage point. The way information is shared and understood can significantly influence the system’s behaviour, impacting everything from decision-making processes to overall system efficiency. Improving communication channels, ensuring transparency, and making sure all stakeholders are heard can lead to more effective decision-making and positive outcomes.

For instance, in our work at We Are Open Co-op, practicing open communication and transparency is central to our project management approach. By sharing progress, challenges, and decision-making processes openly with all stakeholders, we foster a culture of trust and collaboration. This openness extends to how we handle privacy; by being transparent about how we collect, use, and protect data, we build confidence among our partners and clients. Implementing tools that enable open documentation and communication, such as public repositories or shared workspaces, not only keeps everyone informed but also reinforces accountability and integrity in our practices. This small adjustment in how information is shared and protected can lead to significant improvements in project outcomes, ensuring that tasks are completed effectively while respecting privacy concerns.

The power of communication as a leverage point lies in its ability to unify and align the various components of a system. By enhancing the flow of information and ensuring that all voices are heard, you can create a more cohesive, responsive, and effective system.

5. Feedback Loops as Leverage Points

“The major problems in the world are the result of the difference between how nature works and the way people think.” — Gregory Bateson

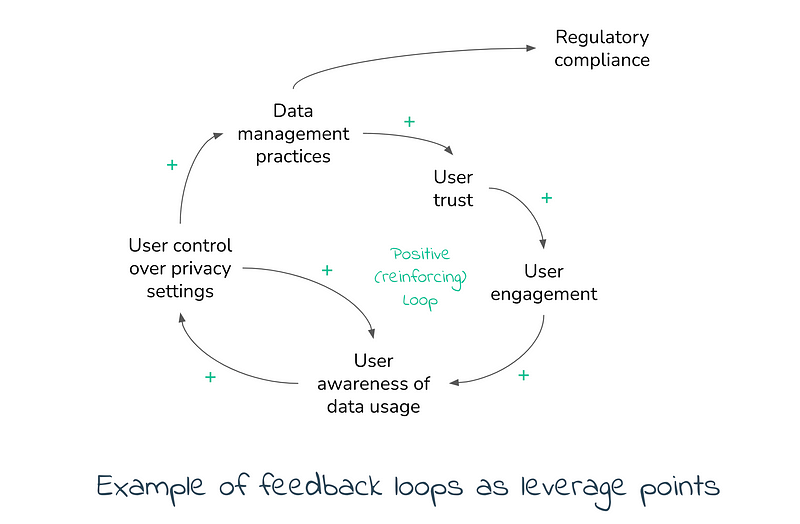

Feedback loops, as discussed in the second post, can also act as leverage points within a system. By altering how these loops operate, you can influence the system’s overall behaviour. Identifying and adjusting these loops — whether reinforcing (positive) or balancing (negative) — can be a powerful way to steer the system toward desired outcomes.

For example, in the context of data privacy, feedback loops between user behaviour and data management practices can be effectively leveraged to enhance privacy protection. By providing users with real-time feedback on how their data is being used and giving them the ability to adjust their privacy settings, you create a positive feedback loop. As users become more aware of how their data is handled, they are often motivated to take greater control over their privacy settings. This increased control leads to further trust in the platform, encouraging users to engage more actively with privacy tools. Over time, this feedback loop can significantly strengthen overall data protection practices, leading to better compliance with regulations and higher user satisfaction.

This example highlights how adjusting feedback loops can lead to substantial changes in system behaviour with relatively simple interventions. By strategically modifying these loops, you can achieve desired outcomes more effectively and sustainably.

Conclusion

Leverage points offer powerful opportunities to influence complex systems with relatively small, strategic actions. By identifying where these points lie and understanding how to use them effectively, you can create meaningful and lasting change within any system. Whether you are looking to improve organisational processes, drive social change, or enhance personal decision-making, the principles of Systems Thinking can help you navigate complexity with greater clarity and purpose.

This post, along with the previous two in this series, provides an introduction to the foundational principles of Systems Thinking and their practical applications. These insights are drawn from my studies toward an MSc in Systems Thinking in Practice through the Open University, and they are just the beginning of what Systems Thinking can offer.

If you’re interested in applying these principles to your work, We Are Open Co-op is here to help you implement effective systemic interventions tailored to your unique challenges. Thank you for following this series — your journey into Systems Thinking doesn’t have to end here. Continue to explore, apply, and refine these concepts, and watch how they can transform the way you approach complex problems.

References

- Ackoff, R.L. (1974). Redesigning the Future: A Systems Approach to Societal Problems. New York: Wiley.

- Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind. San Francisco: Chandler Publishing Company.

- Bateson, M.C. (1994). Peripheral Visions: Learning Along the Way. New York: HarperCollins.

- Beer, S. (1972). Brain of the Firm. New York: Herder and Herder.

- Checkland, P. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Logic: The Theory of Inquiry. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

- Jung, C.G. (1957). The Undiscovered Self. New York: Little, Brown, and Co.

- Meadows, D.H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. White River Junction: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Vickers, G. (1965). The Art of Judgement: A Study of Policy Making. London: Chapman & Hall.

Discussion